Tehran: One Man's Temple of Modern Art

I want to educate students in art. Give something back to society: architect Gholamreza Motamedi created Iran's only private modern art museum, open to all, free of charge.

Here is the story, from Washington Post:

It's the statue of a lion in the front yard, welded from old engine parts, that makes 31 Soheil Alley stand out in a Tehran neighborhood of palatial houses surrounded by high walls. Unlike the barricaded, burglar-alarmed entrances of its neighbors, the door to 31 is wide open, inviting all to enter.

A modest hall gives way to an astonishing seven-story labyrinth of layered-brick passageways, rugged steel staircases and rooms with hidden alcoves. Visitors come upon collections of experimental video art, couches shaped like octopuses and abstract warriors made from pieces of wire.

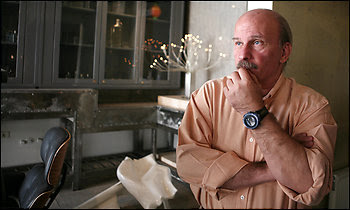

The building, constructed along the slope of a hill, belongs to Gholamreza Motamedi -- art lover, erstwhile dissident and former architect. It houses Iran's only private modern art museum.

Motamedi, 58, designed the entire structure, from the entrance to the exhibition rooms to the coffee shop. And even though he says Iranian authorities have revoked his permission to operate the museum, he opens its doors every day.

I created a space that hides secrets, full of closed atmospheres, Motamedi said. To add to the mystery, there is no charge, not even for the coffee, tea and cakes -- shocking in a country where partaking of culture costs money. A little confusion forces people to think, he said.

Much about the museum and Motamedi seems unusual in the Iran that has taken shape since the 1979 Islamic revolution. The museum is not owned by the state, it exhibits Western and local modern art and design, and its owner has forsaken the chance to fill his pockets by putting his property to a more lucrative use.

I want to educate students in art. Give something back to society, he said, showing off an armchair created by American designers Charles and Ray Eames. You can't find these in Iran. It's good for young Iranian designers to see and feel these objects, to sit on them, Motamedi said.

Many people think I'm insane. Why would one man spend his money on students? Why is the entrance free of charge? But when they come here and see the museum, they tell me there should be much more of these places in Iran, Motamedi said.

The administration of former president Mohammad Khatami gave Motamedi a permit for the gallery when it opened in 2004. They had a somewhat more liberal view of art, he said. But the present government tries to structure art according to its policies of returning to the values of the revolution. So museums here don't show international poster exhibitions, but only posters from Islamic countries, Motamedi continued. Three months ago, they revoked our permit, he said of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. The ministry now wants us to send them pictures of what we plan to exhibit a week before we organize something.

Born to a wealthy family, Motamedi had the sports car, foreign trips and affluent lifestyle that came with being a member of Iran's elite in pre-revolution years. But as oil money poured into the country and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi sought to force a Western lifestyle upon what was then a mostly rural population, Motamedi was struck by the inequality he saw. Rich Tehranis celebrated modernization with champagne and beluga caviar, while peasants continued to work in brickmaking factories and drive taxis.

Motamedi led a double life in the years leading up to the revolution, which ultimately brought to power a group of Shiite clerics. As a young architect, he made a living designing bars and clubs that were often burned down by Islamist revolutionaries. At the same time, he become involved with leftist groups and envisioned an Iran where class differences would be gone and the poor would have a good life. But Motamedi and his comrades lost out to the Islamists, who sentenced him to four years in prison for his membership in parties they deemed illegal.

When Motamedi was released, he and some friends started an advertising agency, cashing in on an economy that boomed after the eight-year war with neighboring Iraq ended in 1988. Art, however, remained his passion, and he later decided to encourage Iranians to focus on the art surrounding them. A poster can be art, a car can be art, a spare wheel can be art. People just need to see it. I hope that when they come to the museum, their eyes will be opened, he said.

Sitting in the coffee shop, Motamedi noted that the revolution opened the way for many Iranians to come in contact with art. In the time of the shah, families didn't allow their children to watch television, because it was regarded as morally corrupting. The same goes for sending their daughters to university in those years. But this has all changed now, he said, noting that Iranian television now has art shows and that more than 65 percent of university students are women.

On one wall, Motamedi has recreated an ancient tablet written by the Persian King Darius I. It's a text of a prayer for the future generation of Iran, to protect them from lies, Motamedi explained. After all those years, it's still relevant.

(Contemporary Art)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home