David Rhode: Held by the Taliban (1)

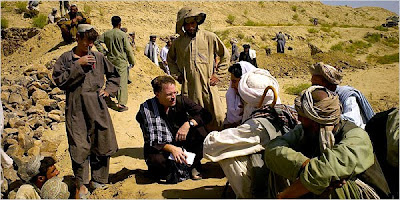

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)Journalist David Rhode was kidnapped by the Taliban inn November 2007 and succeeded to escape in June 2009. Here is his story published by NY Times:

The car’s engine roared as the gunman punched the accelerator and we crossed into the open Afghan desert. I was seated in the back between two Afghan colleagues who were accompanying me on a reporting trip when armed men surrounded our car and took us hostage.

Another gunman in the passenger seat turned and stared at us as he gripped his Kalashnikov rifle. No one spoke. I glanced at the bleak landscape outside — reddish soil and black boulders as far as the eye could see — and feared we would be dead within minutes.

It was last Nov. 10, and I had been headed to a meeting with a Taliban commander along with an Afghan journalist, Tahir Luddin, and our driver, Asad Mangal. The commander had invited us to interview him outside Kabul for reporting I was pursuing about Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The longer I looked at the gunman in the passenger seat, the more nervous I became. His face showed little emotion. His eyes were dark, flat and lifeless.

I thought of my wife and family and was overcome with shame. An interview that seemed crucial hours earlier now seemed absurd and reckless. I had risked the lives of Tahir and Asad — as well as my own life. We reached a dry riverbed and the car stopped. They’re going to kill us, Tahir whispered. They’re going to kill us.

Tahir and Asad were ordered out of the car. Gunmen from a second vehicle began beating them with their rifle butts and led them away. I was told to get out of the car and take a few steps up a sand-covered hillside.

While one guard pointed his Kalashnikov at me, the other took my glasses, notebook, pen and camera. I was blindfolded, my hands tied behind my back. My heart raced. Sweat poured from my skin.

Habarnigar, I said, using a Dari word for journalist. Salaam, I said, using an Arabic expression for peace.

I waited for the sound of gunfire. I knew I might die but remained strangely calm.

Moments later, I felt a hand push me back toward the car, and I was forced to lie down on the back seat. Two gunmen got in and slammed the doors shut. The car lurched forward. Tahir and Asad were gone and, I thought, probably dead.

The car came to a halt after what seemed like a two-hour drive. Guards took off my blindfold and guided me through the front door of a crude mud-brick home perched in the center of a ravine.

I was put in some type of washroom the size of a closet. After a few minutes, the guards opened the door and pushed Tahir and Asad inside.

We stared at one another in relief. About 20 minutes later, a guard opened the door and motioned for us to walk into the hallway.

No shoot, he said, no shoot.

For the first time that day, I thought our lives might be spared. The guard led us into a living room decorated with maroon carpets and red pillows. A half-dozen men sat along two walls of the room, Kalashnikov rifles at their sides. I sat down across from a heavyset man with a patu — a traditional Afghan scarf — wrapped around his face. Sunglasses covered his eyes, and he wore a cheap black knit winter cap. Embroidered across the front of it was the word Rock in English.

I’m a Taliban commander, he announced. My name is Mullah Atiqullah.

For the next seven months and 10 days, Atiqullah and his men kept the three of us hostage. We were held in Afghanistan for a week, then spirited to the tribal areas of Pakistan, where Osama bin Laden is thought to be hiding.

Atiqullah worked with Sirajuddin Haqqani, the leader of one of the most hard-line factions of the Taliban. The Haqqanis and their allies would hold us in territory they control in North and South Waziristan.

During our time as hostages, I tried to reason with our captors. I told them we were journalists who had come to hear the Taliban’s side of the story. I told them that I had recently married and that Tahir and Asad had nine young children between them. I wept, hoping it would create sympathy, and begged them to release us. All of my efforts proved pointless.

Over those months, I came to a simple realization. After seven years of reporting in the region, I did not fully understand how extreme many of the Taliban had become. Before the kidnapping, I viewed the organization as a form of Al Qaeda lite, a religiously motivated movement primarily focused on controlling Afghanistan.

Living side by side with the Haqqanis’ followers, I learned that the goal of the hard-line Taliban was far more ambitious. Contact with foreign militants in the tribal areas appeared to have deeply affected many young Taliban fighters. They wanted to create a fundamentalist Islamic emirate with Al Qaeda that spanned the Muslim world.

I had written about the ties between Pakistan’s intelligence services and the Taliban while covering the region for The New York Times. I knew Pakistan turned a blind eye to many of their activities. But I was astonished by what I encountered firsthand: a Taliban mini-state that flourished openly and with impunity.

The Taliban government that had supposedly been eliminated by the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan was alive and thriving.

All along the main roads in North and South Waziristan, Pakistani government outposts had been abandoned, replaced by Taliban checkpoints where young militants detained anyone lacking a Kalashnikov rifle and the right Taliban password. We heard explosions echo across North Waziristan as my guards and other Taliban fighters learned how to make roadside bombs that killed American and NATO troops.

And I found the tribal areas — widely perceived as impoverished and isolated — to have superior roads, electricity and infrastructure compared with what exists in much of Afghanistan.

At first, our guards impressed me. They vowed to follow the tenets of Islam that mandate the good treatment of prisoners. In my case, they unquestionably did. They gave me bottled water, let me walk in a small yard each day and never beat me.

But they viewed me — a nonobservant Christian — as religiously unclean and demanded that I use a separate drinking glass to protect them from the diseases they believed festered inside nonbelievers.

My captors harbored many delusions about Westerners. But I also saw how some of the consequences of Washington’s antiterrorism policies had galvanized the Taliban. Commanders fixated on the deaths of Afghan, Iraqi and Palestinian civilians in military airstrikes, as well as the American detention of Muslim prisoners who had been held for years without being charged. America, Europe and Israel preached democracy, human rights and impartial justice to the Muslim world, they said, but failed to follow those principles themselves.

During our captivity, I made numerous mistakes. In an effort to save our lives in the early days, I exaggerated what the Taliban could receive for us in ransom. In response, my captors made irrational demands, at one point asking for $25 million and the release of Afghan prisoners from the American detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. When my family and editors declined, my captors complained that I was worthless.

Tahir and Asad were held in even lower esteem. The guards incessantly berated both of them for working with foreign journalists and repeatedly threatened to kill them. The dynamic was not new. In an earlier kidnapping involving an Italian journalist and his Afghan colleagues, the Taliban had executed the Afghan driver to press the Italian government to meet their demands.

Despite the danger, Tahir fought like a lion. He harangued our kidnappers for hours at a time and used the threat of vengeance from his powerful Afghan tribe to keep the Taliban from harming us.

We became close friends, encouraging each other in our lowest moments. We fought, occasionally, as well. At all times, an ugly truth hovered over the three of us. Asad and Tahir would be the first ones to die. In post-9/11 Afghanistan and Pakistan, all lives are still not created equal.

As the months dragged on, I grew to detest our captors. I saw the Haqqanis as a criminal gang masquerading as a pious religious movement. They described themselves as the true followers of Islam but displayed an astounding capacity for dishonesty and greed.

Our ultimate betrayal would come from Atiqullah himself, whose nom de guerre means gift from God.

What follows is the story of our captivity. I took no notes while I was a prisoner. All descriptions stem from my memory and, where possible, records kept by my family and colleagues. Direct quotations from our captors are based on Tahir’s translations. Undoubtedly, my recollections are incomplete and the passage of time may have affected them. For safety reasons, certain details and names have been withheld.

Our time as prisoners was bewildering. Two phone calls and one letter from my wife sustained me. I kept telling myself — and Tahir and Asad — to be patient and wait. By June, our seventh month in captivity, it had become clear to us that our captors were not seriously negotiating our release. Their arrogance and hypocrisy had become unending, their dishonesty constant. We saw an escape attempt as a last-ditch, foolhardy act that had little chance of success. Yet we still wanted to try.

To our eternal surprise, it worked.

On Oct. 26, 2008, I arrived in Afghanistan on a three-week reporting trip for a book I was writing about the squandered opportunities to bring stability to the region. I had been covering Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2001 and was inspired by the bravery and pride of the people in those two countries and, it seemed, their popular desire for moderate, modern societies.

The first part of my visit proved depressing. I spent two weeks in Helmand Province, in southern Afghanistan, and was struck by the rising public support for the Taliban. Seven years of halting economic development, a foreign troop presence and military mistakes that killed civilians had bred a deep resentment of American and NATO forces.

For the book to be as rigorous and fair as possible, I decided that I needed to get the Taliban’s side of the story.

I knew that would mean taking a calculated risk, a decision journalists sometimes make to report accurately in the field. I was familiar with the potential consequences. In 1995, I was imprisoned for 10 days while covering the war in Bosnia. Serbian authorities arrested me after I discovered mass graves of more than 7,000 Muslim men who had been executed in Srebrenica.

My detention was excruciating for my family. Promising I would never put them through such an ordeal again, I was cautious through 13 subsequent years of reporting.

I flew from Helmand to Kabul on Sunday, Nov. 9, to meet with Tahir Luddin, who worked for The Times of London and was known as a journalist who could arrange interviews with the Taliban.

After making some inquiries, Tahir told me that a Taliban commander named Abu Tayyeb would agree to an interview the next day in Logar Province. We could meet him after a one-hour drive on paved roads in a village near an American military base.

Tahir had already interviewed Abu Tayyeb with two other foreign journalists and said he trusted him. He said Abu Tayyeb was aligned with a moderate Taliban faction based in the Pakistani city of Quetta.

The danger, he said, would be the drive itself. Nothing is 100 percent, he told me. You only die once.

I felt my stomach churn. But if I did the interview, the most dangerous reporting for the book would be over. I could return home with a sense that I had done everything I could to understand the country.

Yes,”\ I told Tahir. Tell him yes.

That night, I had dinner with Carlotta Gall, a dear friend and the Kabul bureau chief for The New York Times, and asked her if the interview was a crazy idea. Carlotta said she had never felt the need to interview the Taliban in person and preferred phone conversations. She recommended that we hire a driver to serve as a lookout and end the meeting after no more than an hour.

I also met with a French journalist who had interviewed Abu Tayyeb twice with Tahir. In the fall of 2007, she spent two days filming him and his men as they trained. In the summer of 2008, she spent an evening with them and filmed an attack on a police post.

She pointed out that I was more vulnerable as an American, but she said she thought Abu Tayyeb would not kidnap us. She said she believed that he was trying to use the media to get across the Taliban’s message.

I slept poorly the night before the interview. I got out of bed early and put on a pair of boxer shorts my wife had given me on Valentine’s Day emblazoned with dozens of I love you logos, hoping they would bring good luck.

I left two notes behind. One gave Carlotta the location of the meeting and instructed her to call the American Embassy if we did not return by late afternoon. The other was to my wife, Kristen, in case something went wrong.

I walked outside and met Tahir and Asad Mangal, a friend he had hired to work as a driver and lookout. As we drove away, Tahir suggested that we pray for a safe journey. We did.

Dressed in Afghan clothes and seated in the back, I covered my face with a scarf to prevent thieves from recognizing me as a foreigner. Most kidnappings in and around Kabul had been carried out by criminal gangs, not the Taliban.

From the car, I sent Carlotta a text message with Abu Tayyeb’s phone number. I told her to call him if she did not hear from me. If something went wrong along the way, Abu Tayyeb and his men would rescue us. Under Afghan tradition, guests are treated with extraordinary honor. If a guest is threatened, it is the host’s duty to shelter and protect him.

We arrived at the meeting point in a town where farmers and donkeys meandered down the road. But none of Abu Tayyeb’s men were there. Tahir called Abu Tayyeb, who instructed us to continue down the road.

Moments later, I felt the car swerve to the right and stop. Two gunmen ran toward our car shouting commands in Pashto, the local language. The gunmen opened both front doors and ordered Tahir and Asad to move to the back seat.

Tahir shouted at the men in Pashto as the car sped down the road. I recognized the words journalists and Abu Tayyeb and nothing else. The man in the front passenger seat shouted something back and waved his gun menacingly. He was small, with dark hair and a short beard. He seemed nervous and belligerent.

I hoped there had been some kind of mistake. I hoped the gunmen would call Abu Tayyeb, who would vouch for us and order our release. Instead, our car continued down the road, following a yellow station wagon in front of us.

The gunman in the passenger seat shouted more commands. Tahir told me they wanted our cellphones and other possessions. If they find we have a hidden phone, Tahir said, they’ll kill us.

Tell them we’re journalists, I said. Tell them we’re here to interview Abu Tayyeb.

Tahir translated what I said, and the driver — a bearish, bearded figure — started laughing.

Who is Abu Tayyeb? I don’t know any Abu Tayyeb, he said. I am the commander here.

They are thieves or members of another Taliban faction, I thought. I knew that what we called the Taliban was really a loose alliance of local commanders who often operated independently of one another.

I looked at the two gunmen in the front seat. If we somehow overpowered them, I thought, the men in the station wagon would shoot us. I did not want to get Asad and Tahir killed. My arrest in Bosnia had ended peacefully after 10 days. I thought the same might occur here.

One of the gunmen said something and Tahir turned to me. They want to know your nationality, he said. I hesitated and wondered whether I should say I was Canadian. Being an American was disastrous, but I thought lying was worse. If they later learned I was American, I would instantly be declared a spy.

Tell them the truth, I told Tahir. Tell them I’m American.

Tahir relayed my answer and the burly driver beamed, raising his fist and shouting a response in Pashto. Tahir translated it for me: They say they are going to send a blood message to Obama.

BY the time I met face to face later that day with Atiqullah, our kidnapper, I still did not know which Taliban faction had abducted us.

A large man with short dark hair protruding from the sides of his cap, he appeared self-assured and in clear command of his men. He also seemed suspicious of us, which worried me. I knew many Taliban believed all journalists were spies.

With Tahir translating, we explained that we had been invited to Logar Province to interview Abu Tayyeb, the Taliban commander. I said I had worked as The Times’s South Asia correspondent from 2002 to 2005. I described articles I had written during the war in Bosnia and told him that Serbian Orthodox Christians had arrested me there after I had exposed the massacre of Muslims.

Atiqullah remained unmoved. He denied our request to call Abu Tayyeb or a Taliban spokesman. He controlled our fate now, he announced. Atiqullah handed me the notebook and pen his gunmen had taken from me and ordered me to start writing.

American soldiers routinely disgraced Afghan women and men, he said. They forced women to stand before them without their burqas, the head-to-toe veils that villagers believe protect a woman’s honor. They searched homes without permission and forced Afghan men to lie on the ground, placing boots on the Afghans’ heads and pushing their faces into the dirt. He clearly viewed the United States as a malevolent occupier.

He produced one of our cellphones and announced that he wanted to call The Times’s office in Kabul. I gave him the number, and Atiqullah briefly spoke with one of the newspaper’s Afghan reporters. He eventually handed me the phone. Carlotta, the paper’s Kabul bureau chief, was on the line. I said that we had been taken prisoner by the Taliban.

What can we do?” Carlotta asked. What can we do?

Atiqullah demanded the phone back before I could answer. Carlotta — the most fearless reporter I knew — sounded unnerved.

Atiqullah turned off the phone, removed the battery and announced that we would move that night for security reasons. My heart sank. I had hoped that we would somehow be allowed to contact Abu Tayyeb and be freed before nightfall. As we waited in the house, I thought Carlotta would be calling my family and editors at any minute to inform them that I had been kidnapped.

I awoke before dawn to the sound of the guards performing a predawn prayer with Tahir and Asad. We had been taken to a small dirt house and then spent the day trapped in a claustrophobic room with our three guards. Measuring roughly 20 feet by 20 feet, its only furnishings were the carpet on the floor and a dozen blankets.

One of our guards introduced himself as Qari, an Arabic expression for someone who had memorized the Koran. He later said he was one of the fedayeen, an Arabic term the Taliban use for suicide bombers.

Food arrived at mealtimes, and no one was beaten. Yet Tahir grew increasingly worried. These guys are really religious, he whispered to me at one point. They’re really religious. They’re praying a lot.

Confined to the room for most of the day, I found it increasingly suffocating. By now, I was sure my family had heard the news.

Several hours after sunset, we were hustled into a small station wagon.

We have to move you for security reasons, said Atiqullah, who was sitting in the driver’s seat, his face still concealed behind a scarf. Arab militants and a film crew from Al Jazeera were on their way, he said.

They’re going to chop off your heads, he announced. I’ve got to get you out of this area.

As we drove away, I asked for permission to speak. Atiqullah agreed, and I told him we were worth more alive than dead. He asked me what I thought he could get for us. I hesitated, unsure of what to say. I was desperate to keep us alive.

I knew that in March 2007, the Afghan government exchanged five Taliban prisoners for the Italian journalist after the Taliban executed his driver. Later, they killed his translator as well. My memory of the exchange was vague, but I thought money was included. In August 2007, the South Korean government had reportedly paid $20 million for the release of 21 Korean missionaries after the Taliban killed two members of the group.

Money and prisoners, I said.

How much money? Atiqullah asked.

I hesitated again.

Millions, I said, immediately thinking I would regret the statement.

Atiqullah and one of his commanders looked at each other.

Over the next hour, the conversation continued. Atiqullah promised to do his best to protect us. I promised him money and prisoners.

As we wound our way through steep mountain passes, Atiqullah asked for the names and professions of my father and brothers. I told him the truth. Given the unusual spelling of my last name, I thought he could easily find my relatives online.

My father was a retired insurance salesman, I said. One of my brothers worked for an aviation consulting company. A stepbrother worked for a bank. I thought being forthright was helping convince him that I was a journalist, not a spy.

For the next four days, we lived with Qari, the suicide bomber, in another small dirt house. On one afternoon, he allowed us to sit outside in a small walled courtyard.

He even let Tahir play a game on a cellphone. But when Tahir asked for the phone a second time, Qari shouted that we planned to send a text message to the Kabul bureau of The Times. Suddenly enraged and irrational, he denounced us as liars. He picked up his Kalashnikov, pointed it at Tahir’s chest and threatened to shoot him.

Tahir stared back, unmoved. Pashtunwali — an ancient code of honor practiced by ethnic Pashtuns in Afghanistan and Pakistan — prevented each man from showing fear and losing face.

Asad and I stepped in front of Tahir. We begged Qari to put down his gun. Lutfan, lutfan, I said, using a local expression for please. Qari lowered his weapon but motioned for Tahir to step into an outer room.

Through the wall, I heard Tahir begin praying in Arabic. I heard a thump and Tahir cried out, Allah! A second thump and Allah! Several minutes later, Tahir walked back into the room, crawled under a blanket and began moaning. Qari had beaten him on the back with his rifle.

Qari unnerved me. Earnestly reciting hugely inaccurate propaganda about the West I had seen on jihadi Web sites, Qari seemed utterly detached from reality. Other guards joked that he had mental problems.

In my mind, Qari and Atiqullah personified polar ends of the Taliban. Qari represented a paranoid, intractable force. Atiqullah embodied the more reasonable faction: people who would compromise on our release and, perhaps, even on peace in Afghanistan.

I did not know which one represented the majority. I wanted to believe that Atiqullah did. Yet each day I increasingly feared that Qari was the true Taliban.

The following day, Atiqullah arrived to move us again. During the ride, he said we would be taken to a place where I could receive bottled water and we could call our families. He promised to protect me.

I will not kill you, he said. You will survive.

I insisted that he promise to save Tahir and Asad as well. You will not kill the three of us, I said. It has to be the three of us.

Initially, Atiqullah refused. For days, I raised the issue over and over, remembering that under the Pashtunwali code a promise of protection should be ironclad. At one point, I suggested that he cut off my finger instead of harming Tahir and Asad.

Later that day, he finally promised to protect all three of us. I give you my promise, he said, as I lay down in the back of the station wagon. I will not kill any of the three of you.

Then, he said, Let’s kill Asad first, and laughed.

The following afternoon, a new commander arrived. A bone-thin man with a long beard and one arm, he got into the driver’s seat and guided us through barren, rock-strewn territory, steering the car and shifting gears with lightning-quick movements of his one hand.

At sunset, he stopped the vehicle, and Atiqullah announced that we would have to walk through the mountains. A large American base blocked the path in front of us, he said. The one-armed commander gave me a pair of worn loafers, and another guard gave me his jacket.

As we walked, I understood why Western journalists had grown enamored of the anti-Soviet Afghan resistance fighters in the 1980s. Under a spectacular panorama of stars, we wound our way along a steep mountain pass. Emaciated Taliban fighters carried heavy machine guns with little sign of fatigue. Their grit and resilience seemed boundless.

I thought about making a run for it but had not had a chance to talk it over with Tahir and Asad. I also knew that the half-dozen guards would quickly shoot us.

As the hike continued, I grew suspicious. Atiqullah — who had promised to carry me if needed — proved to be in poor shape. On one of the steepest parts of the ascent, he stopped, sat on a rock and panted.

Nine hours after we set out, the sun rose and the hike dragged on. Asad approached me when the guards lagged behind, pointed at the way ahead and whispered, Miram Shah. Miram Shah is the capital and largest town in North Waziristan, a Taliban and Qaeda stronghold in Pakistan’s lawless tribal areas. North Waziristan was the home of some of the Taliban’s most hard-line members. If we were headed there, we were doomed.

After 11 hours, our hike finally ended. The guards lighted a fire, and we warmed our hands as we waited for a vehicle to pick us up.

Exhausted and anxious, I told myself that Asad was wrong and Atiqullah was right. I told myself that we were walking into southern Afghanistan, not Pakistan. I told myself we would survive.

(Zoon Politikon)

Labels: David Rhode

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home