David Rhode: Held by the Taliban (6) Epilogue

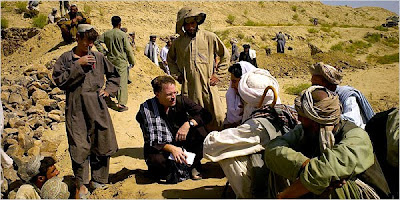

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)

Journalist David Rhode was kidnapped by the Taliban inn November 2007 and succeeded to escape in June 2009. Here is the epilogue of his story published by NY Times:

Five weeks after our escape, Asad crossed from Pakistan into Afghanistan, called his family and said he was free.

Ten days later, I spoke with him by phone. Asad said the guards had slept until dawn on the night Tahir and I escaped. At first, they thought we were in the bathroom. Then they realized we were gone.

Asad said he was accused of knowing about our escape plan. A Taliban commander then chained and held him underground for 17 days. For three of those days he was beaten, he said.

Asad’s family sent a tribal delegation to press his captors to release him. Asad said that after a guard left him alone on July 27, he fled, found a taxi and took it to the Afghan border.

In our phone call, Asad denied cooperating with the guards during our captivity and said that he had carried a gun because the Taliban had ordered him to do so. In the end, I believe that Asad played along with the Taliban to survive.

Upon my return to New York, I learned that a wide array of people had worked for our release, including family members, colleagues, government officials and security consultants.

A number of Afghan and Pakistani men also offered to try to obtain information about our whereabouts or to gain our release. Some volunteered, others asked for money. During that time, two of the Afghan men died in ambushes, but it is not known whether those attacks were related to work on our case.

Determining the truth of events in the border areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan is notoriously difficult. The current fighting in the region makes it even more so. Killings are rarely investigated. Disputes, vendettas and rumors are constant.

After I returned home, I discovered that my captor’s fabrications were even larger than I had realized. Abu Tayyeb, it turned out, had made his name in the late 1990s by killing a group of Afghan prisoners who opposed the Taliban. He is believed to be hiding in Karachi in southern Pakistan.

His claim that I had told the military of his location on the day of our Nov. 10 interview was false. There had been no military operation.

The video of us trudging through the snow in January was never broadcast. Al Jazeera ran a brief promotional segment but then did not broadcast the full video at the request of The Times.

Virtually all of the statements Abu Tayyeb made to me regarding the negotiations turned out to be false. The Afghan government never agreed to exchange prisoners for the three of us. And the United States did not offer to trade us for the remaining Afghan prisoners at Guantánamo Bay. After our escape, rumors circulated that a ransom had been paid or our guards bribed. My family and The New York Times paid no ransom. The Times has decided not to make public its efforts to secure our release because details could endanger correspondents and others working in the region.

American government officials worked to free us, but they maintained their longstanding policy of not negotiating with kidnappers. They paid no ransom and exchanged no prisoners. Pakistani and Afghan officials said they also freed no prisoners and provided no money.

Security consultants who worked on our case said cash was paid to Taliban members who said they knew our whereabouts. But the consultants said they were never able to identify or establish contact with the guards who were living with us.

False reports persist. On Sept. 13, The Sunday Times in London reported that $9 million was paid for our release. Then it issued a full retraction.

The Taliban continue to abduct journalists. On Sept. 6, fighters in the Afghan province of Kunduz kidnapped a New York Times correspondent, Stephen Farrell, and the Afghan journalist working with him, Sultan Munadi, as they reported on a NATO bombing that had killed many civilians.

Four days later, a raid by British commandos freed Stephen, but Sultan was killed, along with a British soldier and an Afghan woman. Sultan was a good friend. He was the father of two and was home on a break from studying in Germany.

My suspicions about the relationship between the Haqqanis and the Pakistani military proved to be true. Some American officials told my colleagues at The Times that Pakistan’s military intelligence agency, the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI, turns a blind eye to the Haqqanis’ activities. Others went further and said the ISI provided money, supplies and strategic planning to the Haqqanis and other Taliban groups.

Pakistani officials told my colleagues that the contacts were part of a strategy to maintain influence in Afghanistan to prevent India, Pakistan’s archenemy, from gaining a foothold. One Pakistani official called the Taliban proxy forces to preserve our interests.

Meanwhile, the Haqqanis continue to use North Waziristan to train suicide bombers and bomb makers who kill Afghan and American forces. They also continue to take hostages.

I feel enormous gratitude for everything that was done on our behalf. We were extraordinarily fortunate to have escaped from the Taliban mini-state in Pakistan’s tribal areas. Countless others have not been — and will not be — so lucky.

For much of their captivity, David Rohde and his colleagues were held in Miram Shah, above, in the North Waziristan region of Pakistan, the stronghold of a Taliban faction

For much of their captivity, David Rohde and his colleagues were held in Miram Shah, above, in the North Waziristan region of Pakistan, the stronghold of a Taliban faction(Zoon Politikon)

Labels: David Rhode

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home