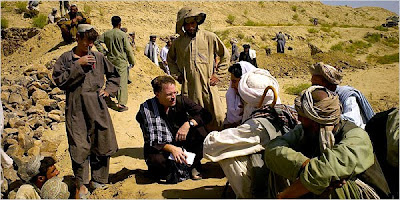

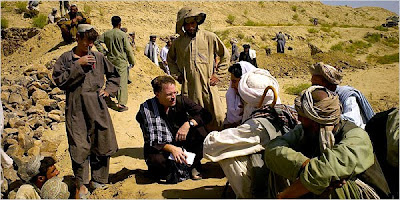

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)

(Journalist David Rhode interviewing peasants in Southern Afghanistan, one year before he was kidnapped)Journalist

David Rhode was kidnapped by the Taliban inn November 2007 and succeeded to escape in June 2009.

Here is his story published by

NY Times:

I stood in the bathroom of the Taliban compound and waited for my colleague to appear in the courtyard so we could make our escape. My heart pounded. A three-foot-tall swamp cooler — an antiquated version of an air-conditioner — roared in the yard a few feet in front of me. I feared that the guards who were holding us hostage might wake up and stop us. I feared even more that our captivity would drag on for years.

It was 1 a.m. on Saturday, June 20, in Miram Shah, the capital of the North Waziristan tribal agency in Pakistan. After seven months and 10 days in Taliban captivity, I had come to a decision with

Tahir Luddin, the Afghan journalist I had been kidnapped with, to try to make a run for it.

By then, we had concluded that our captors — a Taliban faction led by the

Haqqani family — were not seriously negotiating for our release. In the latest of countless lies, they announced that the United States would free all the Afghan prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in exchange for us. We found the statement ludicrous and insulting. As they had a dozen times in the past, our captors claimed that a deal was near. Then nothing happened.

Tahir and I had decided that I would get up first that night and go to the bathroom without asking the guards for permission. If the guards remained asleep,

Tahir would follow. Twenty feet away, on a shelf outside the kitchen, was a car towrope we planned to use to lower ourselves down a 15-foot wall ringing the compound. I had found it two weeks earlier and hidden it beneath a pile of old clothes.

Several minutes went by, but

Tahir did not come out of the room. I stared intently at the entrance to the living room where we slept side by side with the guards — roughly 15 feet away and directly across the courtyard from the bathroom — and waited for

Tahir to emerge. I had pulled his foot to rouse him before I crept out of the room. He had groaned and, I assumed, awakened.

As the minutes passed, I wasn’t sure what to do. I stood in the darkened bathroom and wondered if

Tahir had changed his mind. If the guards caught us, they might kill me, but they would definitely kill

Tahir. Part of me thought it was wrong even to have agreed to do this. After seven months in captivity, I wondered if we were capable of making rational decisions.

Even if we made it over the wall, we would have to walk through Miram Shah to get to a nearby Pakistani base. The town teemed with Afghan, Pakistani and foreign militants. Whoever caught us might be far less merciful than our current guards. Once on the base, we might encounter Pakistani military intelligence officials or tribal militia members who were sympathetic to the Taliban and would hand us back to the

Haqqanis.

Yet I desperately longed to see my wife and family again. And I hated our captors so vehemently that I wanted them to get nothing in exchange for me. I pushed ahead.

Following a backup plan that

Tahir and I had discussed that afternoon, I stepped out of the bathroom and picked up a five-foot-long bamboo pole leaning against the adjacent wall. I walked to the living room window and peered inside to make sure the guards were still asleep.

Beside me, the swamp cooler covered up the noise I made. Inside the room, a ceiling fan hummed. I opened the window, pointed the pole at

Tahir’s side and poked him. I quickly walked back to the bathroom, leaned the pole against the wall and stepped inside.

Still,

Tahir did not appear. I was convinced that he had changed his mind. It wasn’t fair of me, I thought, to have expected a man with seven children to risk his life.

Then, like an apparition,

Tahir’s leg emerged from the window. His upper body and head followed and, finally, his second leg. As he stood up, I rushed out of the bathroom to meet him and kicked a small plastic jug used for ablutions. It skidded across the ground, and I motioned to

Tahir to freeze, fearing that the noise would wake the guards.

Tahir and I stared at each other in the darkness. No guards appeared from the living room. Taking a few steps forward, I whispered in

Tahir’s ear.

We don’t have to go, I said.

We can wait.

Go get the rope, he said.

Inside the living room,

Asad Mangal, the young driver who had been taken hostage with

Tahir and me, was sound asleep with the guards.

Several weeks earlier, we decided we could no longer trust

Asad, who had begun cooperating with the guards and carrying an assault rifle they had given him. That afternoon,

Tahir and I made a gut-wrenching decision to leave without him, fearing that he would tell the guards of our escape plans — as he had before.

Our rupture with

Asad had become the darkest aspect of an already bleak captivity. Over the many months, the solidarity the three of us shared immediately after the kidnapping on Nov. 10 frayed under the threat of execution and indefinite imprisonment.

In December,

Tahir and

Asad expressed fury at me for exaggerating what our captors could receive for us in ransom. After being told that crews were on their way to film our beheadings, I had blurted out that our captors could receive prisoners and millions of dollars if we were kept alive.

I repeatedly apologized to

Tahir and

Asad, saying I had been trying to save us. But they called me a fool.

Over the course of the spring,

Tahir said

Asad told the guards that

Tahir once had encouraged him to escape on his own. He said

Asad told the guards that I was an American spy.

Finally,

Tahir said he had whispered to

Asad we should escape one night two weeks earlier.

Asad did not respond. Days later, a guard announced that he had heard that

Tahir was trying to escape.

Yet I also knew that

Asad was under enormous pressure. As the driver, he would probably be the first one killed by the Taliban. He could be cooperating with the guards in order to survive.

Still, I did not trust him. If

Tahir and I spoke with

Asad about escaping for a second time, he could once more inform the guards. At the very least, we would squander an opportunity we might never have again. At worst,

Tahir and I would be killed.

We had arrived at the Miram Shah compound the first week of June. It was our ninth location in the tribal areas; we had been shuttled by our captors among homes in North and South Waziristan.

As I had done when we arrived in each new place, I swept floors and picked up trash to create a sense of order. It was then that I found the car towrope beside some wrenches and motor oil. The discovery, I thought, was the first stroke of good luck in our seven months in captivity. Thinking we might be able to use the rope during an escape, I hid it under an old shirt and pants.

In the days that followed, I tried to think of ways we could flee. When the guards let us sit on the roof with them at dusk, I noticed that it was surrounded by a five-foot-high wall. If we could hoist ourselves over it, I thought, we could use the rope to lower ourselves to the street.

At the same time,

Tahir surveyed the area around the house when the guards took him with them to buy food and watch cricket games once or twice a week. He determined that the compound was closer to Miram Shah’s main Pakistani militia base than any other house we had been held in.

Tahir and I kept our conversations brief about how we could escape, worrying that the guards or

Asad would overhear us.

On the afternoon of June 19, electricity returned to Miram Shah for the first time since fighting nearby cut power lines a week earlier. It was a fortuitous development. Electricity meant the swamp cooler and ceiling fan would help conceal any noise we made when we fled.

Already angry at new lies the guards had told us that morning about the negotiations, we agreed to try to escape that night.

Tahir would keep the guards up late playing checkah, a Pakistani version of Parcheesi. If they were tired, they would sleep more soundly. Our plans for how to get over the wall were in place. Unfortunately, we disagreed about what to do after that.

Tahir said the Pakistani militiamen who guarded the military base would shoot us if we approached them at night. He said we should hike 15 miles to the Afghan border. I responded that we would never make it that far without being caught. Going to the Pakistani base was a risk we had to take. If we could surrender to an army officer, I said, he would protect us.

As we continued to argue, the guards returned to the room, and

Tahir and I had to stop speaking. For the rest of the evening, we were never alone again. Our plan had no ending.

Tahir kept the guards up late as we had discussed. By roughly 11 p.m., everyone was in bed. I lay awake, trying to listen to the guards’ breathing to figure out whether they had fallen asleep.

I blinked over and over in the darkness but saw no difference when my eyes were open or closed. It was as if I were blind. I turned around at times to look at the orange light on the swamp cooler to make sure I could still see.

Anxious, I tried to calm myself by praying. In February, a Taliban commander who had been pressing me to convert to Islam told me that if I said

forgive me, God 1,000 times each day our captivity might end. I had done as he had suggested, with no results. But I did not care.

The prayers soothed me and passed the time. Each day, I would stare at the ceiling and say

forgive me, God 1,000 times while the guards took naps. Counting on my fingers, it took me roughly 60 minutes to reach 1,000.

That night, waiting to make sure the guards were sound asleep, I asked God to forgive me 2,000 times.

In truth, I expected the escape attempt to fail quickly. I thought a guard would wake up as soon as I tried to leave the room. I would say I was going to the bathroom, walk to the toilet, return a few minutes later and go back to sleep. I would feel better the next morning for at least having tried.

Instead, to my amazement, our plan was actually working. After

Tahir and I made it to the courtyard, I retrieved the rope and we crept up a flight of stairs leading to the roof.

Tahir tied the rope to the wall surrounding the roof. Placing his toe between two bricks, he climbed to the top and peered at the street below.

The rope is too short, he whispered after stepping down.

I shifted the knot on the rope to give it more length, pulled myself up on the wall and looked down at the 15-foot drop. The rope did not reach the ground, but it appeared close.

I glanced back at the stairs, fearing that the guards would emerge at any moment.

We don’t have to go, I repeated to

Tahir.

It’s up to you.

I got down on my hands and knees,

Tahir stepped on my back and lifted himself over the wall. I heard his clothes scrape against the bricks, looked up and realized he was gone.

I grabbed his sandals, which he had left behind, and stuffed them down my pants. I climbed over, momentarily snagged a power line with my foot, slid down the wall and landed in a small sewage ditch. I looked up and saw

Tahir striding down the street in his bare feet. I ran after him.

For the first time in seven months, I walked freely down a street. Glancing over my shoulder, I didn’t see any guards emerge from our house, which looked smaller than I had expected.

We headed down a narrow dirt lane with primitive mud-brick walls on either side of us. Makeshift electrical wires snaked overhead in what looked like a densely populated neighborhood.

We walked into a dry riverbed and turned right. I kept slipping on the large sand-covered stones and felt punch-drunk. I caught up to

Tahir and handed him his sandals.

My ankle is very painful,

Tahir said, as he slipped them on and continued walking.

I can’t walk far.

A large dark stain covered his lower left pant leg. I worried that he had ripped open his calf on his way down the wall. At the same time, my left hand stung. I noticed that the rope had made a large cut across two of my fingers.

Where are we going? I asked

Tahir as we quickly made our way down the riverbed, afraid someone would see or hear us.

There is a militia base over there,

Tahir said, gesturing to his left.

I don’t trust them.

Neither did I. Earlier,

Tahir had told me there was a checkpoint maintained by a Pakistani government militia near the house. Turning ourselves in there would be a gamble, I thought. I still believed that our best chance was to surrender to a military officer on the Pakistani base in Miram Shah.

We have to go to the main base, I said.

Impossible,

Tahir said, continuing down the riverbed.

The guards said that Arabs and Chechens watch the main gate 24 hours a day.

The Taliban would recapture us,

Tahir believed, before we got to the base. I started to panic. We had made it over the wall but did not know where we were going.

Despite his ankle,

Tahir seemed determined to hike 15 miles to the Afghan border. As we walked, we argued over which way to go.

We have to go to the Pakistani base, I told

Tahir.

Striding ahead, he didn’t respond. Dogs began barking from one of the walled compounds to our right.

We can’t make it to the border, I said.

We have to go to the base.

Tahir continued walking, but after a few minutes he complained about his ankle.

There is too much pain, he said.

We stopped and I pulled up his pant leg. His calf had not been cut. The dark stain on his pants was from the sewage ditch we had both landed in outside our compound.

There is another gate,

Tahir said, changing his mind.

Come.

I waited for Taliban fighters to emerge from the darkness, but none did.

Tahir told me to put a scarf I was carrying over my head.

If anyone stops us, your name is Akbar and my name is Timor Shah, he said.

Act like a Muslim.

My sense of time was distorted, but it seemed as though we had been walking in the darkness for 5 to 10 minutes. I did not feel free. If anything, I was more frightened. I worried that an even more brutal militant group would capture us.

We left the riverbed and walked down an alleyway between compounds for about 50 yards. We arrived at a two-lane paved street.

This is the main road in Miram Shah,

Tahir whispered.

To our left was a vacant stretch. To our right stood a gas station with four pumps and several shops. Dim light bulbs hung outside and illuminated the area. I silently questioned why

Tahir was leading us down the center of the road where we could be easily spotted.

Suddenly, shouts erupted to our left and I heard a Kalashnikov being loaded.

Tahir raised his hands and said something in Pashto. A man shouted commands in Pashto. I raised my hands as my heart sank. The Taliban had recaptured us.

In the faint light, I saw a figure with a Kalashnikov standing on the roof of a dilapidated one-story building. Beside the building was a mosque with freshly painted white walls. The building and mosque had concertina wire and earthen berms in front of them.

If you move,

Tahir said,

they will shoot us.

Then,

Tahir said words I could scarcely believe.

This is the base.

We had made it to the Pakistanis.

I held my hands high in the air and dared not move an inch. A nervous Pakistani guard could shoot us dead as we stood in the street. With my long beard, scarf and clothes I looked like a foreign suicide bomber, not a foreign journalist.

Another voice came from inside the building. It sounded as if the guard was waking up his comrades. One or two more figures appeared on the roof and aimed more gun barrels at us.

The Pakistani guard on the roof intermittently spoke in Pashto with

Tahir. I heard

Tahir say the words for

journalist,

Afghan and

American.

My arms began to burn, and I struggled to slow my breathing. I desperately tried not to move my hands.

Tell them we will take off our shirts, I told

Tahir, thinking the Pakistani guards might fear that we were suicide bombers who wore vests packed with explosives.

Tahir said something in Pashto, and the man responded.

Lift up your shirt,

Tahir said. I immediately obliged.

The guard spoke again.

He is asking if you are American,

Tahir said.

I am an American journalist, I said in English, surprised at the sound of my own voice in the open air.

Please help us. Please help us.

I kept talking, hoping they would recognize that I was a native English speaker.

We were kidnapped by the Taliban seven months ago, I said.

We were kidnapped outside Kabul and brought here.

Do you speak English? I said, hoping one of the Pakistani guards on the roof understood.

Do you speak English?

The guard said something to

Tahir.

They are radioing their commander,

Tahir said.

They are asking for permission to bring us inside.

Tahir pleaded with the guards to protect us under the traditional honor code of Pashtunwali, which requires a Pashtun to give shelter to any stranger who asks. He begged them to take us inside the base before the Taliban came looking for us.

About two or three minutes passed. The Pakistani guards stood behind sandbags on the roof. Above us, stars glittered in a peaceful, crystal clear sky.

For the first time that night, it occurred to me that we might actually succeed. Escape — an ending I never dreamed of — might be our salvation. I held my hands still and waited.

Several minutes passed, and

Tahir and I grew nervous.

Please allow us in the mosque,

Tahir said.

Please let us inside.

The Pakistani guard on the roof said they were waiting for the senior officer to arrive.

Tahir asked what we should do if the Taliban drove down the road. The guard said that we should dive behind the dirt embankment, and that they would open fire on anyone who approached. But they still declined to let us on the base.

Tahir complained to me about the pain in his arms as he held them in the air. His ankle hurt as well.

Please wait, Tahir, I said, encouraging him to keep his hands in the air.

Please wait. We’re so close.

Tahir asked for permission to sit on the ground, and the Pakistani guard granted it.

Tahir sat down and groaned. He seemed exhausted.

Soon after, the Pakistani guard said we could walk toward the mosque. With our hands in the air, we crossed over the surrounding berm unsteadily. As the loose soil gave way, we both nearly lost our balance. I worried that we would be shot if we slipped and fell.

Lie down on the ground,

Tahir said.

If you move, they will shoot us.

Soon after, a senior Pakistani officer arrived, and

Tahir told me to stand up. The officer stood a few feet from us on the other side of the concertina wire. He spoke with

Tahir in what sounded like a reassuring tone.

He is a very polite person,

Tahir said.

We are under their protection. We are safe.

In one moment, the narrative of our captivity reversed itself. The powerlessness I had felt for months began to fade. We were achingly close to going home.

I thanked the officer in Pashto, Urdu and English, desperate to win his trust.

How are you? the senior officer said in English.

How are you? I replied, trying again to demonstrate that I was an American.

At this point,

Tahir and I had been standing outside the concertina wire for 15 or 20 minutes. We still needed to get inside the base.

We offered to take off our shirts, and the officer told us to do so. I watched

Tahir step unsteadily over the concertina wire and into the base.

Come,

Tahir said.

Come.

I followed

Tahir inside, and the senior officer and several Pakistani guards shook my hand.

Thank you, I said to them in English, over and over.

Thank you.

The politeness of the Pakistani guards amazed me. I knew we could still be handed over to the Taliban, but I savored the compassion we were receiving from strangers. For the first time in months, I did not feel hostility.

They let us put our shirts on and drove us in a pickup truck toward the center of the base. I stared at

Tahir and slapped him on the back. We were both in shock.

Thank you, I said.

Thank you.

I asked

Tahir to tell the guards that I wanted to call my wife,

Kristen. I needed to somehow communicate to the outside world that we were on a Pakistani base. If we could get word to American officials, it would be extraordinarily difficult for the Pakistanis to hand us back to the

Haqqanis.

We arrived in the center of the base, and I got out the back of the truck. A row of well-lighted, white one-story offices sat 50 feet away on the other side of a neatly manicured lawn. It was the first green grass I had seen in seven months. I walked across it and relished the sense of openness and safety. The guards brought us to a clean, modern office with a large desk and couches along the walls.

After several minutes, a young Pakistani captain who spoke perfect English introduced himself as the base commander. He looked as if he had just gotten out of bed.

After explaining our kidnapping and escape, I asked him if I could call my wife. He hesitated at first and then said he would try to find a phone card to make a long distance call.

As we waited,

Tahir spoke in Pashto to the various militia members on the base. A doctor cleaned and bandaged the cuts on his foot and my hand.

Tahir laughed and his face beamed as he spoke. I had never seen him so happy. But after several minutes, his face darkened.

David, I feel terrible about Asad,

Tahir said of our driver.

What have we done?

I looked out the window in the direction of Miram Shah and wondered whether the guards who had been holding us captive had awakened yet. When they did, they would be furious.

We had no choice, I said, trying to rationalize abandoning

Asad. I wondered if our escape could prompt our captors to kill him. I prayed that they would be merciful.

About an hour later, a soldier arrived with a phone card, and I wrote my home number on a white slip of paper. The captain dialed the phone on his desk and handed me the receiver.

The phone in my apartment back in New York rang repeatedly and no one answered. Finally, the answering machine picked up and I listened to my wife’s cheerful voice ask callers to leave us a message. Our escape still seemed like a dream. The machine beeped, and I spoke in an unsteady voice.

Kristen, it’s David, I said.

It’s David. Please pick up.

I repeated the words several times. Fearing that the tape on the answering machine would run out, I finally blurted out,

We’ve escaped.

Someone picked up the receiver in New York.

David, a woman’s voice said.

It’s Mary Jane.

My mother-in-law had answered.

We’ve escaped and are on a Pakistani military base, I told her.

Fearing retaliation by the Taliban, I asked her to call

The Times immediately and tell them to evacuate

Tahir’s and

Asad’s families from their homes in Kabul, as well as the people in the newspaper’s bureau there.

I spent the next several minutes describing our exact location. I gave her the names of the tribal area, town, base and commanding officer. I told her she needed to contact American officials and ask them to help evacuate us. I wanted the Pakistani officer to hear that the American government would soon know we were on his base. At the end of the conversation, I apologized to her for all of the pain and worry I had caused.

Just come home safe, she said.

Thirty minutes passed, and the captain agreed to let me make another call to try to reach my wife. With each passing minute, I began to believe that we were finally safe and would return home.

The phone rang. This time,

Kristen picked up.

David? she said, breathlessly.

David?

Kristen, I said, savoring the chance to utter the words I had dreamed of saying to her for months.

Kristen, I said,

please let me spend the rest of my life making this up to you.

Yes, she said.

Yes.

(Zoon Politikon)Labels: David Rhode

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 1/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 1/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 2/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 2/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 3/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 3/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 4/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 4/10

Images from Distant Thunder: Part 5/10

Images from Distant Thunder: Part 5/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 6/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 6/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 7/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 7/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 8/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 8/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 9/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 9/10 Image from Distant Thunder: Part 10/10

Image from Distant Thunder: Part 10/10