Two Views about Boris Yeltsin's Legacy

Two views about Boris Yeltsin's legacy. One comes from Bill Clinton, in Sunday's NY Times . The other comes from Fareed Zakaria, in the recent issue of Newsweek.

Bill Clinton considers that Boris Yeltsin had two major objectives, to make sure Russia will never again fall under Communism and to form a solid partnership between a democratic Russia and the West.

He also stood up to Russian nationalists who might have pushed the former Soviet Union into uncontrollable directions. Says Mr. Clinton, he (Yeltsin) made the compromises necessary to get Ukraine, along with Belarus and Kazakhstan, to give up its Soviet-era nuclear weapons. He pulled Russian troops out of the Baltic states. He made Russia part of the diplomatic solution to the crises in Bosnia and Kosovo. And much as he opposed the enlargement of NATO, he accepted the right of Central European states to join the alliance and signed a cooperation agreement between Russia and the alliance.

As for Fareed Zakarina, he has a totally different view: we now forget that what Yeltsin did on top of that tank was to issue unilateral decrees. While they may have been suited to that emergency, they became standard procedure in Yeltsin's tenure. He ruled by fiat, firing judges, governors and legislators who crossed him. He pursued an economic privatization program that led, intentionally or not, to chaos and corruption. He waged a ruinous war in Chechnya that still drains Russia. He implemented what the historian (and Yeltsin supporter) Richard Pipes called a coup d'état to install Vladimir Putin as his successor.

Here is a copy of each article

-Bill Clinton's article:

As I walked behind Boris Yeltsin’s coffin at Novodevichy Cemetery on Wednesday, I found myself thinking about the man I worked with closely for nearly eight years and the role he played in changing the world, mostly for the better.

Every time I met with him, Mr. Yeltsin left no doubt that he had two objectives above all others. The first was to make sure that the Russian people never again had to live under communism, or autocratic ultranationalism. The second was to form a solid, lasting partnership between a democratic Russia and the West.

On the big issues that came up between us, Mr. Yeltsin and I had our differences, and his position was often made more difficult by economic problems and political pressures. But at the end of the day, he almost always did the right thing. He insisted on respecting Russia’s borders with the other old Soviet republics. That meant standing up to Russian nationalists who might have plunged the former Soviet Union into the kind of chaos that engulfed Yugoslavia.

He made the compromises necessary to get Ukraine, along with Belarus and Kazakhstan, to give up its Soviet-era nuclear weapons. He pulled Russian troops out of the Baltic states. He made Russia part of the diplomatic solution to the crises in Bosnia and Kosovo. And much as he opposed the enlargement of NATO, he accepted the right of Central European states to join the alliance and signed a cooperation agreement between Russia and the alliance.

Mr. Yeltsin really wanted the Group of 7 industrialized nations to take Russia in as an eighth member. The other G-7 leaders and I agreed, because of the progress Russia was making in developing a pluralistic democracy with a free press and a vigorous civil society, and because of his critical cooperation on security issues. We saw the creation of the G-8 as a vote of confidence in him and his country’s future.

The last time I saw Mr. Yeltsin during my presidency was in June 2000, six months after he became the first leader of Russia to step down voluntarily as part of a constitutional transition. Though the burdens of office and his heart surgery had taken a toll on his health, he still had his trademark bear hug and smile. He clearly thought he had done the right thing in stepping down early and in selecting as his successor Vladimir Putin, who had the intelligence, energy and stamina the country needed to get Russia’s economy on track and handle its complicated politics.

I told him I was impressed by what I had seen of President Putin but wasn’t sure he was as comfortable with or committed to democracy as Mr. Yeltsin. Mr. Yeltsin replied that we would have disagreements as Russia found its way into the future, but that President Putin would not turn the clock back and we would find a way to work together.

I saw Mr. Yeltsin one more time, when I went back to the Kremlin for the 75th birthday party President Putin held for him last year. He seemed in good health and at peace with himself and his work.

Boris Yeltsin was intelligent, passionate, emotional, strong-willed and courageous. He wasn’t perfect, and he had to contend with staggering political and economic challenges as he led Russia away from centuries of authoritarian rule. But lead he did. At the end of the cold war, Russia and the world were lucky to have him.

History will be kind to my friend Boris.

- Fareed Zakaria's article:

Much of the fulsome praise for Boris Yeltsin has come from outside Russia. While Russians continue to have a dyspeptic view of the grand old man, foreign leaders have rushed in to remind the world what a courageous and pivotal figure he was. It was Yeltsin, they remind us, who dismantled the Soviet empire. It was his decision to voluntarily leave office that created Russian democracy. We all remember Yeltsin on top on that tank in 1991, when he almost singlehandedly turned back a coup d'état.

I share some of this admiration for Boris Yeltsin. He will surely stand as a figure on the hinge of history—yet he pointed Russia in the wrong direction. Compare Russia with China. In the early 1990s, they were the two most important countries in the world that lay outside the sphere of democratic, capitalist states. Russia had by far the stronger hand. In those days it was still regarded as the second most important world power, whose blessings were needed for any big international endeavor—whether the first gulf war or Middle East peace negotiations. It had a GDP of $1 trillion (in purchasing-power parity), the world's second largest military and its second largest pool of technically trained personnel. Perhaps most significant, it had the most abundant endowment of natural resources on the face of the earth. And with Yeltsin as president, the country had a charismatic leader who could leverage this hard and soft power.

China by contrast was an international pariah. It had just gone through the shame of the Tiananmen Square massacres. Its per capita GDP was just one third that of Russia's, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. Its educational and technological system was still in shambles, having been shut down during the Cultural Revolution. Its leaders—a group of seemingly narrow-minded engineers—were cautiously introducing reforms to a country still limping after decades of Mao Zedong's mad gambits at home and abroad.

We now forget that what Yeltsin did on top of that tank was to issue unilateral decrees. While they may have been suited to that emergency, they became standard procedure in Yeltsin's tenure. He ruled by fiat, firing judges, governors and legislators who crossed him. He pursued an economic privatization program that led, intentionally or not, to chaos and corruption. He waged a ruinous war in Chechnya that still drains Russia. He implemented what the historian (and Yeltsin supporter) Richard Pipes called a coup d'état to install Vladimir Putin as his successor.

Look at the two countries today: though the Russian economy has surged because of high oil and commodity prices, China's is now six times larger. Even more interesting is the political trajectory. Russia, in almost every dimension, has become less free over the past decade. Its economy is increasingly state-dominated, its polity controlled and its people cowed. Consider that in the past 10 years, after Iraq, Russia has been the country in which the largest number of journalists have been killed. (And while many of the deaths in Iraq were accidental, this is true of almost none of them in Russia.)

China, by contrast, has seen greater economic, legal and social reform every year. This year, finally, the Communist Party adopted guarantees of private property and greater government transparency. (For those who dismiss China's reforms because they are "merely" economic, recall that for John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, the right to private property was at the heart of individual liberty.)

My point is not that China is freer than Russia. It is not. But for a decade, the arrow in Russia has been moving backward, while in China it is moving—slowly—forward.

This divergence between the Russian and Chinese models has had powerful implications around the world. Russia has become an example—but a negative example. The Chinese leadership has privately admitted to having watched Yeltsin's reforms and decided that they produced economic chaos, social instability and no growth. (Russia's GDP contracted by 20 percent during the 1990s.) Instead of similar shock therapy—which Bill Clinton's Russia hand Strobe Talbott accurately characterized as "too much shock, too little therapy"—China chose a cautious, incremental path. "We must cross the river by feeling the stones with our feet," said Deng Xiaoping. Rather than shutting down state-owned enterprises, Beijing chose to grow the economy around them, so that the state-owned portion kept shrinking and its problems became more manageable.

Look around the world, from Vietnam to Egypt, and you see officials studying China's economic reforms. I have not come across a single official anywhere who has ever claimed to be emulating Russia's path from communism.

Why did these two pivotal nations go down the roads they did? Part of the reason is that Russia is afflicted by the curse of natural resources, part that China is a more pragmatic society. History, culture and demography all play a part. But so do people. And it is worth wondering what might have been had Boris Yeltsin, in those critical years, turned Russia along a different course.

Labels: Fareed Zakaria

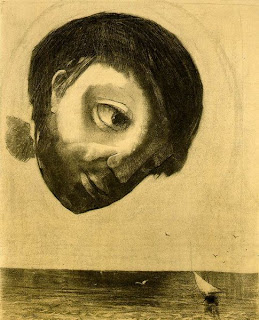

Corot

Corot