Listening Koncertas Stan Brakhage

Kenneth Noland, In the Garden. The girl in the middle, marked with an X. Could be Alice, exploring delicately a garden of wonders? Or one of my granddaughters? Bianca? Or Daria?

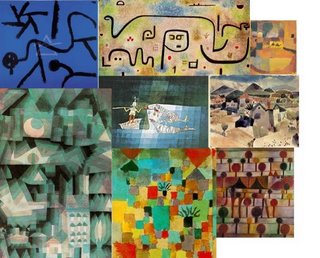

Noland would later go on his own way, here he is still in the universe of Paul Klee. But it's Noland, for sure. Such a delicate sense of the color! And another wonder, there is a suggestion of bidimensionality, the way Byzantine icons organize their space, in the same time a suggestion of perspective.

I was yesterday at the Phillips Collection and I considered selecting ten images for my own imaginary: ten paintings telling me something special just in that particular moment. My first choice was this Noland.

This was yesterday. I am listening now SYR 6 , the record of Sonic Youth: Koncertas Stan Brakhage. He didn't want music for his movies. He didn't want plot, either. The cinematographic language in its purity, nothing more. Almost 400 movies - his quest for the purity of cinematographic language.

Brakhage didn't want music for his films, however James Tenney composed music for Interim, for Desistfilm, for Loving, for Matins, for Christ Mass Sex Dance. A musical complement, or a parallel? I have just ordered a CD with some pieces by Tenney. My own search to discover parallel structures in painting, movie, music, the language structures of Noland, Brakhage, Tenney.

Here is the second choice, not far from the universe where Noland was following the roads of Klee. It's Adolph Gottlieb, Seer, made in 1950. Trying to have the eye of a primitive, like Klee did. The pictographs of Gottlieb, his alphabet to tell us the unseen. Klee, and Noland, and Gottlieb, in search of the universe of kids and primitives, to be able to see beyond the obvious.

The concert of Sonic Youth was a homage to Brakhage who had died one year earlier. Only this homage was against his wishes, I don't make my films out of caprice. I feel they need a silent attention.

His declaration seems arrogant. It is not. I was watching Regen, the movie made by Joris Ivens, in 1928. The music was kind of chansonette, subtle and poetic, only the movie was much more - I watched Regen then without music and the whole poetry inundated my senses.

I am curios to listen Tenney.

My third choice: Georgia O'Keeffe, Ranchos Church.

Today Ingmar Bergman died. I'm listening Koncertas Stan Brakhage, recorded one year after Brakhage's death.

I saw many times this Ranchos Church. It brings me always in mind a scene which comes again and again in The Ashes of Time, of Wong Kar-Wai. The place where the characters come to meet each other for matters of life and death.

I would enter and pray in this Ranchos Church, only it attracts and scares me altogether. There is nothing but God in that church, you are far from your world, in front of the turning point in life and death. You and the Eye of God.

And here is the fourth choice: the Road Menders of Van Gogh. The menders are only weak shapes, the trees are inflamed, like in fire, like crazy dancers. The vitality of the background, the road that will go further towards Klimt and Art Nouveau.

The music of Koncertas Stan Brakhage Prisiminimui: a music for movies that detest music.

Is it dark humor? Well, I saw only four of his movies, so far, I am waiting for a dvd with more films by Brakhage - it will come probably in a couple of days - this is the music for those movies. I'm trying to enter in their world by this loose jazz. Music to imagine movies that detest music. Trying to get into the Weltanschaung of Brakhage, by using music, against his wishes.

My fifth choice: Franz Marc, Deer in Forest (there are two versions, this is the first). It reminds me of the art of Pirosmani.

I'm trying to imagine myself in a small tea house in Tbilisi, with Pirosmani hanging around, listening the Sonic Youth: Koncertas Stan Brakhage. How would it sound there? Metallic pulses, catalytic drums, and railing strings fall apart, and skeletal guitar radiates brief noir themes? (SYR 6)

Rockwell Kent, Tierra del Fuego, the sixth choice. It's like a photo and I like it precisely for this reason. By being like a photo, it is a formal declaration: this is not the reality, it is an image, with it own reality.

Bergman, with all dilemmas and paradoxes of the Protestant universe. Whether a believer or not, you belong to your universe. The terrible focus on predestination: it means actually the inevitability of Eternal Punishment. The characters of Bergman live under damnation. A fallen world, far from God: it means happiness is impossible. Love is far; here is only lust and repentance. And now comes the paradox: if damnation is certain and happiness is unattainable, you are free, nothing more to loose, and you challenge everything. And so the Protestant universe paradoxically questioned all taboos. No sacred value was exempted: neither church, nor family, nor sexuality.

Augustus Vincent Tack, Windswept, the seventh choice. The painting was made around 1900, in New England (in Leyden, Massachusetts).

Windswept, the snow mountain, the snow painting: the white is almost absolute. Again alone, on the edge.

The first movie made by Brakhage, Interim: a boy and a girl meet by pure chance. He just went down from an enormous viaduct, she was coming from the opposite direction. Industrial landscape. The street is crossed by a railway, and a train is just passing, slowly. The two teenagers wait, each one on the other side. The train has passed, they notice each other and smile. They start to talk and walk a bit together. There is a stream nearby and they sit down. The rain starts suddenly and a small crumbling shelter is at view. They run inside and start to embrace and kiss for a brief moment. The rain ends, they come out. He leaves, taking the stairs to the viaduct, she waits for another train to pass, slowly. There is a story here, but it's only the pretext. The movie builds a small Neo-Realist world and plays a little bit inside. That's all. Brakhage was 19 years old. Tenney scored the movie. He was 18. It was 1952.

Robert Spencer, Across the Delaware, the eighth choice. The town across is New Hope, in Bucks County. I was there many times. The small restaurants and boutiques on the main street keep still some bohème air - it was once the place of the Pennsylvanian Impressionists: the New Hope School. By that time, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Impressionism was still new in America, and the Pennsylvanians were considered the democrats of the new style. Compared to the artists that created in New England (like Tack or Weir), their focus was much more on the everyday life, the subjects they were interested in were much more in the popular universe.

Unglassed Windows Cast a Terrible Reflection, the second film of Brakhage, made in 1953. About 20 minutes, like the first one, Interim. Only the universe is totally different. Now it's the landscape of Stalker. Only we should note that Tarkovsky made his movie in 1979!

Let's be clear: Stalker is to be understood on multiple levels. Here, in the movie of Brakhage, there is no such thing. The plot is only a pretext again, like in Interim. A group of teenagers make an excursion in the mountains, the car breaks, the driver is busy to fix the thing, the others look around. A group of strange wooden houses on the hill. Kind of shacks. Unfinished while crumbled. Through the unglassed windows, the light from within the houses plays with the light from outside. They start to explore. Soon each one looses the others and is alone, like prisoner in a labyrinth. Each new step brings each one in a totally new place. Through the unglassed windows light plays with darkness. They find each other, only to start a fight. One boy is killed. The other steps on a wooden board, looses his equilibrium and dies in the fall. We don't know the reaction of the others, because the camera moves to the ridge of the trees and the movie ends.

So, no multiple levels of understanding, like in Stalker. Only the same growing dread on each step in an alien territory, rendered here in pure cinematographic language, in changes of light rhythm. For Brakhage, it seems, plot is only a pretext, to explore light in motion, in interaction with the eye of the onlooker.

Julian Alden Weir, Woodland Rocks, the ninth choice. It reminded me a photo that I had seen some time ago at Phillips: Martha's Vineyard by Aaron Siskind. Each with a different story. The painting of Weir is a moment in a mountain journey, the photo of Siskind is a gate where space ends.

Phillips Collection is hosting an exhibition devoted to American Impressionists, artists from New York, from New England, from Pennsylvania, Hassam, Prendergast, Weir, Lawson, Tack, Twachtman, Spencer, Robinson, Luks, among others.

Yesterday there was also the last day for another exhibition at Phillips: the Washington Color School, artists who became known in the sixties, Noland, Gene Davis, Morris Louis, Willem de Looper, Alma Thomas, Mehring, Downing, Paul Reed. Impressionists in between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and Colorists from the sixties and beyond... Works from one exhibition were finding the balance in the other. A room with paintings by Georgia O'Keeffe, Van Gogh, Franz Marc, Rousseau le Douanier was making the transition easier.

I am thinking again at Brakhage's movie, Unglassed Windows Cast a Terrible Reflection (by the way, titles were perhaps not his strongest point). The last image, of the ridge of trees, suggested me another dimension of the movie.

Paul Schrader studied the transcendental dimension in the movies of Ozu, Bresson and Dreyer. He noted in their movies three steps: the everyday, the disruption, the stasis. Each of their movies starts by presenting a normal situation of life, where everything is comprehensible, and the characters are in control. Unexpected events create a growing tension, the situation is more and more incomprehensible, the characters loose more and more the control, everything evolves up to a disruptive moment. The movie's coda is an image that does not explain the incomprehensible, does not resolve the disruption, but transcends it. Schrader names the final step stasis because it is kind of a frozen view of the reality. So at the end we accept the incomprehensible as we realize that all that happened finds a reason in a superior order.

Well, the movie of Brakhage starts with a group of youngsters in an excursion. There is an erotic suggestion, there is a possible love triangle, but every character seems to be in control. It is the banality of the everyday.

The car breaks and all that follows leads to the disruptive moment, the death of the two boys. Here Brakhage is a master of the cinematic language: the growing tension is rendered by subtle changes of light rhythm.

The coda does not explain the reality, only transcends it. The image of the trees makes us realize that there is a superior order of things, and all events have their reasons above our understanding.

It is interesting to analyze in this view the other movie of Brakhage that I have seen, The Way to Shadow Garden, made in 1954. It was his fourth film. 11 minutes long. This time the plot is no more, it is a pure symbolic film.

A young boy walks through the night. The storm is approaching. He enters his room, closes the windows, but looses gradually the control. Though he tries to do normal actions, to take a glass of water, to read a book, etc, the room becomes his trap. He breaks the glass and gouges his eyes with the splinters. He leaves tSpnecerhe room only to find himself in the shadow garden: the image turns to negative, the darkness is white, his eyes are white. His skin is black, the flowers are black.

I believe that here we have a negative stasis: the transcendental (the shadow garden) does not bring the solace, and man remains prisoner of space. And space for Brakhage means light in motion in dialog with our subjectivity. It would be interesting to make a parallel between Brakhage and Moholy-Nagy (Lichtspiel: Schwartz - Weiss - Grau) or Schlemmer (Das Triadische Ballett)

Edward Weston, Shells, the tenth choice. A photo made in 1927. His nudes taking the shape of his shells, his shells celebrating the beauty of his nudes.

Yesterday Ingmar Bergman died. I was too tired to finish this message, so here I am, again in front of my laptop. Today Michelangelo Antonioni passed away.

(By Brakhage)

(Van Gogh)

Labels: transcendent, Van Gogh