Cartile pe care le citim au fiecare o viata proprie, care curge alaturi de viata noastra, cu visuri, cu asteptari, uneori cu impliniri, alteori cu dezamagiri, o viata in care ani la rand nu se intampla nimic si deodata vin lucruri neasteptate. Este o viata care aproape tot timpul are un singur martor, pe cel care a citit cartea… dar sunt momente in care viata cartii citite este atat de plina incat forteaza participarea mai multor martori.

In ziua cand am implinit doisprezece ani au venit sa ma sarbatoreasca mai multi colegi de la scoala, asa cum se petrecea in fiecare an. Si ca de fiecare data, darurile au fost carti.

Despre una dintre aceste carti vreau sa vorbesc. Nu am citit-o imediat. Cred ca au trecut cateva luni bune pana am luat-o sa o citesc, dar atunci nu am mai lasat-o din mana pana nu am terminat-o.

Se numea

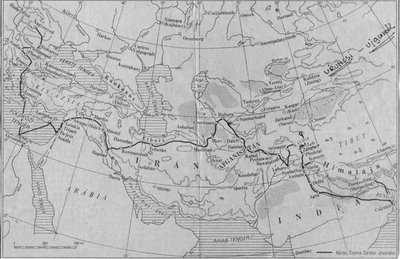

Drumul cel Mare, era o traducere din limba maghiara. Pe autor il chema Korda Istvan, nu mai citisem nimic de el. Pe web am gasit deunazi o imagine a editiei in limba maghiara.

Citisem cu catva timp inainte o alta carte tradusa din limba maghiara, a lui Moricz Zsigmond, se numea

Fii bun pana la moarte – citisem acolo despre incercarile maghiarilor de a afla tinutul lor de origine – banuit a fi pe undeva prin Asia Centrala – il numeau Magna Hungaria. Acum citeam despre cel care facuse

Drumul cel Mare, plecase sa gaseasca Magna Hungaria.

Körösi Csoma Sandor, puiul de secui, care si-a urmat toata viata visul lui din copilarie, sa mearga sa gaseasca Magna Hungaria. A trait in prima jumatate a veacului al nouasprezecelea.

Avea un talent urias pentru limbile straine. Familie de tarani saraci - tatal l-a retras de la scoala si l-a trimis cu oile, Sandor pazea oile si invata de unul singur latina, cu o carte cu fragmente din Virgiliu. Va invata in timpul asta si romaneste, de la ciobanii romani. Va ajunge spre sfarsitul vietii sa cunoasca paisprezece limbi straine, una din ele fiind tibetana.

Dar acum era doar un copil, retras de la scoala si trimis cu oile, care invata de unul singur latina. Un nobil maghiar din tinut infiintase o scoala pentru copiii de secui mai saraci, iar Sandor a ajuns acolo.

Si de atunci avea sa se pregateasca pentru

Drumul cel Mare. Va strange ban peste ban, va dormi toata viata pe podea, pentru a se cali – dascalii trageau nadejde ca va ramane pana la urma la scoala, ca profesor – dar el va starui in visul lui. Cineva ii va fura toate economiile, el o va lua de la capat.

L-au trimis la universitatea din Götingen pentru doi ani, se va intoarce de acolo si mai decis sa plece sa descopere tinutul de origine, Magna Hungaria.

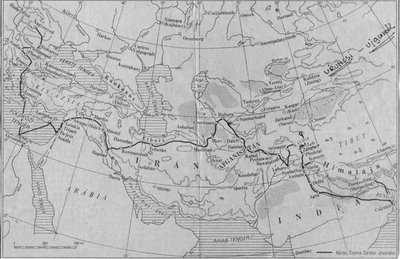

De abia la 36 de ani va pleca. Cu postalionul, prin Bucuresti spre Constantinopol. De acolo va lua o corabie spre Asia Mica. La Alep intalneste un negustor armean care ii da o scrisoare de recomandare catre un var din Teheran. Drumurile le va face de acum cu cate o caravana, sau de unul singur. O epidemie de ciuma se ia la intrecere cu el, il ajunge din urma in cate un oras, el paraseste orasul in graba, pleaca mai departe, epidemia o ia inaintea lui si il asteapta in noul loc de popas. Arabi, iranieni, armeni, afgani – zonelor de ses sau de desert le urmeaza lanturi de munti, caldurilor uscate le urmeaza zapezi – si dupa vreun an si ceva Körösi ajunge in India.

Aici incepe imediat sa se intereseze daca poate intra in China – intalneste intr-un han cativa negustori chinezi care ii povestesc despre o anumita regiune in care locuitorii vobesc o limba foarte diferita de a lor.

In ochii autoritatilor britanice, Körösi pare un vagabond suspect, asa ca este arestat. Va fi interogat de un colonel foarte scortos – care insa ii va intelege geniul – si va sti si cum sa il foloseasca. Körösi va petrece urmatorii cinci ani intr-o manastire budista, si va alcatui

Dictionarul Tibetan – Englez si Gramatica Tibetana. Va munci alaturi de un calugar budist, Sangye Phuntsock, care va deveni cel mai bun prieten al lui.

O manastire budista asezata pe un varf de munte, se poate ajunge la ea doar cu funicularul. Cinci ani de truda. Erau inca tineri cand au inceput munca, si Körösi, si Sangye Phuntsock, calugarul. Dupa cinci ani amandoi arata ca niste oameni batrani.

Dar

Dictionarul Tibetan era gata.

Körösi a continuat sa viseze la continuarea

Drumului cel Mare.

Avea de acum patruzeci si sase de ani cand Sangye Phuntsock, calugarul cu care alcatuise

Dictionarul Tibetan, a reusit sa-i obtina viza de intrare in China.

Si Körösi a pornit din nou la drum. Avea patruzeci si sase de ani. A ajuns in nordul Indiei, la Darjeeling, si de acolo nu a mai putut inainta. Era prea istovit. A murit la Darjeeling – taina originii maghiarilor avea sa fie dezlegata peste vreo suta de ani, de alti carturari.

Am citit cartea pe nerasuflate.

Si au trecut anii si peste mine.

Cred ca aveam de acum aproape patruzeci de ani cand am avut ocazia sa citesc o alta traducere din limba maghiara – se numea

O calatorie in Transilvania anului una mie noua sute patru zeci si trei – autorul era Meliusz Joszef. O carte foarte interesant scrisa, astazi am numi-o postmoderna. Transilvania sfasiata de Dictatul de la Viena. Un intelectual maghiar ramas in partea de sud a Transilvaniei, facand o calatorie in orasele transilvane din zona ramasa in componenta Romaniei, gandindu-se la orasele transilvane din zona ocupata de Ungaria, meditand la destinul acestei provincii. Si intr-unul din capitole a venit vorba si de Körösi Csoma Sandor.

Am reluat cartea citita in copilarie. Acum o citeam cu alti ochi. De abia acum sesizam amanunte peste care trecusem prea usor. Poate cel mai mult m-a impresionat acum staruinta in implinirea visului – Körösi a reusit sa porneasca la drum cand avea treizeci si sase de ani. Cati dintre noi mai au entuziasm si curaj la treizeci si sase de ani? In locul lui, oricine altcineva ar fi ramas la treizeci si sase de ani profesor la scoala unde isi petrecuse tineretea. Si probabil ca din cand in cand s-ar fi gandit cu melancolie la un vis din copilarie care nu avea cum sa se implineasca.

Au mai trecut vreo doi sau trei ani.

Am fost trimis cu niste treburi de serviciu la Targu Mures. Citisem intr-un ziar ca in oras exista o statuie a lui Körösi Csoma Sandor. Intrebam trecatorii, dar nimeni nu stia sa ma lamureasca.

Pana intr-o seara. M-am dus sa vizitez Biblioteca Teleki. Era sapte si jumatate seara, programul bibliotecii era pana la ora opt. Eram impreuna cu un coleg de serviciu.

O doamna care lucra acolo ne-a aratat salile bibliotecii. Parea destul de obosita si de plictisita – ar fi vrut poate sa plece mai devreme acasa si acum trebuia sa isi mai piarda timpul cu doi vizitatori neasteptati. Asa incat prezentarea pe care ne-a facut-o era foarte seaca si simteam o invitatie muta sa plecam mai repede.

Am intrebat-o,

Doamna, puteti va rog sa imi spuneti unde se afla statuia lui Körösi Csoma Sandor?

S-a schimbat deodata la fata.

De unde stiti de el? I-am istorisit in cateva cuvinte istoria cartii pe care o citisem.

Veniti cu mine, mi-a spus. Am urmat-o intr-o camera unde se afla o casa de fier in perete. A deschis-o si mi-a aratat

Dictionarul Tibetan.

Prietenul ei please pe urmele lui Körösi si ajunsese si el pana la Darjeeling. La intoarcere ii daruise ei

Dictionarul Tibetan. Drumul il epuizase si pe el, si murise la scurt timp dupa aceea.

Si acum rasfoiam

Dictionarul Tibetan si intelegeam ca eram martor la una din acele intamplari neasteptate din viata fiecarei carti pe care o citim de-al lungul vietii noastre.

Totul avea o noima. Primisem cartea in dar in ziua in care implineam treisprezece ani. Si viata cartii isi urmase firul ei, pentru ca trebuia sa ajunga aici, sa ma puna in fata

Dictionarului Tibetan – am inteles ca avusesem o datorie, si fata de Körösi, si fata de Korda Istvan, si fata de Meliusz Joszef, si fata de prietenul doamnei din Targu Mures – si acum ne aflam intr-o concelebrare cei trei martori – eu, care citisem cartea a carei viata cursese in paralel cu viata mea, doamna bibliotecara de la Teleki, care pastra

Dictionarul in amintirea prietenului ei care isi daduse viata pentru a retrai visul lui Körösi – si colegul meu de serviciu care urmarea scena in tacere, intelegand ca acolo se petrecea un moment extraordinar.

Si datoria fata de prietenul meu de demult, cel care mi-a daruit cartea. Colegul meu de clasa din scoala primara si din liceu,

Robert Goldstein, cel care visa mereu la plecarea in Israel – aprobarea avea sa ii vina cand era de acum in primul an de facultate, la Arhitectura. Am aflat ca a murit apoi, pe front, in razboiul de sase zile. Si mi-am dorit atunci sa fie o greseala, mi-am dorit sa aflu ca de fapt traieste. Au trecut de atunci atata amar de vreme, eu inca imi doresc sa aflu ca de fapt

Robert traieste.

(A Life in Books)

(A Life in Books)Labels: Körösi Csoma Sandor